Ever since Edwin Drake struck oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859, his discovery of the seemingly innocuous black liquid would soon propel the world into a new era of industrialization and modernization. Today, oil is the most traded commodity in global markets, and its presence can be traced to every corner of the world. It has provided the ease of transportation, the revolution of heating, and the creation of plastics; however, the history of oil and the oil market exposes a far more complex, controversial system. From Rockefeller’s market manipulation to multiple oil shocks to the creation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), oil is a commodity that countries vie for. In fact, OPEC is a “permanent, intergovernmental organization to co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among Member Countries” (OPEC, 2021). Founded in 1960 in response to American price cuts and competition with the Soviet Union, OPEC has been shrouded with controversy due to its heavy involvement in international affairs, exploitation of oil-importing countries, and market manipulation. Some point to these traits as defining characteristics of a cartel, which, by definition, is “a formal agreement among firms to agree on prices, total industry output, market shares, allocation of customers, bid-rigging, and the division of profits” (OECD, 2021). Thus, with OPEC’s increasing breadth of power and influence, the key question that must be addressed is to what extent does OPEC fit the definition of a cartel?

Although proponents cite OPEC’s involvement in the 1970 Arab Oil Embargo and the organization’s significant efforts to collude on global oil supplies during bi-yearly Ministerial Meetings, OPEC is not a cartel because it does not exemplify the traits of price or quantity fixing as it struggles to effectively collude, is largely controlled by Saudi Arabia, has left sufficient market share for its competitors, and acts as a modest force of market stabilization.

This paper will first provide a literature review of the available scholarly research already conducted on this topic. Subsequently, this paper will outline three distinct arguments as to why OPEC is not a cartel and address any potential limitations and counterarguments. First, OPEC is a fragmented organization that does not safeguard countries from cheating in the form of over and under production. Secondly, Saudi Arabia’s share of oil production dwarfs that of other member nations, creating a dominant producer and fringe nation dynamic. Lastly, OPEC does not infringe on any WTO or OECD disputes and simultaneously serves as a modest force for market stabilization. This paper will conclude with an overview of OPEC’s indispensable role and lasting influence on global markets.

Literature Review

In the 1940’s, the world oil market was once governed by seven transnational oil companies called the Seven Sisters, who “colluded to manipulate price and production” (Library of Congress, 2021). However, in 1950, with the threat of increasing Soviet oil production, the US enacted two major prices cuts leading to the Gentlemen’s’ Agreement in 1959 and the ultimate creation of OPEC. With OPEC seemingly having a large effect on global markets, its policies, especially in the volatile 1970’s and deflated 1980’s markets, have been under scrutiny in scholarly circles due to significant quota deviations from member countries.

In “The Limits of OPEC in the Global Oil Market”, Brown University’s Jeff Colgan argues that OPEC “if ever constrains or influences the oil production rate of its member states” (Colgan, 2013). He argues that OPEC itself has outlived its mandate and its effectiveness in the political arena has waned. Furthermore, he makes the leap that OPEC has been riding the wave of perceived market power and perpetuating the misconception of influence, illustrating the façade OPEC has masqueraded to bring its members to international supremacy and favorable trading terms it experiences today.

Other scholarly research shares an even stronger sentiment. For instance, James Smith, Chair of Oil and Gas at Southern Methodist University, characterizes the organization in “Behavioral Test of the Cartel Hypothesis”, as “much more than a non-cooperative oligopoly, but less than a frictionless cartel” (Smith, 2005). He builds his argument upon the idea of a bureaucratic syndicate, where members are dragged down by the cost of enforcement, most evident from the constantly changing membership of non-core states, preventing the true vision of OPEC from emerging.

In Steven Plaut’s “OPEC is not a cartel”, the Israeli economist points towards Saudi Arabia, who provides 31% of total OPEC production and 1/6th of world production, as the moderating force within the organization preventing OPEC from charging the highest prices possible due to Saudi Arabia’s “fear [of] a military confrontation with the consuming countries” as the rest of the states become price takers with limited policy action (Plaut, 1981). On the other hand, Senior Economist at the US Government Accountability Office Pedro Almoguera believes OPEC’s behavior is the definition of Russia and Saudi Arabia in “Cournot competition in the face of a competitive fringe constituted by non-OPEC members”, suggesting the presence of a duopoly and unstable pricing schemes as a result (Almoguera, 2011). Other competing theories include the Stackelberg Model put forth by Abdulrahman Al-Sultan, citing the “cartel’s core members collude and jointly act as a Stackelberg leader versus other non-core members” (Al-Sultan, 1993).

Quantitative research has also addressed the issue of OPEC’s controversial framework. Most notable research has stemmed from the cointegration and causality tests originally conducted by Griffin in 1985, refined by Salehi-Isfahni in 1987 and finalized by Carol Dahl and Mine Yucel in 1989. Dahl and Yucel’s research was groundbreaking because they were one of the first to systematically test OPEC’s policies through a complex model including “static and dynamic variables” such as inventory, invested capital, interest rates and extraction costs from 1971 to 1986 (Dahl, 1989). Their research concluded with only Algeria’s behavior seeming to fit with the definition of a cartel due to its significant negative coefficient when comparing its production to total OPEC production (Dahl, 1989). Gurcan Gulen, who holds a PhD from Boston College, also conducted cointegration tests and his findings seem to fit the same narrative that “the organization does not seem to act as a cohesive whole” (Gulen, 1996).

In pure economic terms, a perfectly competitive market prices its goods equal to the marginal costs of producing it. However, a true cartel charges higher than the equilibrium prices, not only generating significant profits but also lowering consumer surplus as whole. Those who argue that OPEC is a cartel believe in the idea that OPEC members actively implement and follow through with quota limits to collude in the market with restricted competition.

Scholars subscribe to this belief, with Kyle Hyndman, Professor of Economics at the University of Texas, citing that OPEC is a cartel as he “empirically test[s] the time periods OPEC can optimize their aggregate quota for the highest returns” (Hyndman, 2007). Moreover, in “Twenty-five years of Prices and Politics”, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Fellow Ian Skeet argued that OPEC’s price management in 1973 granted it political independence to continue to operate as a cartel and continues to do so in the integrated world today by granting its members autonomy and control over world supply (Skeet, 1988). Lastly, in Charles Doran’s “OPEC Structure and Cohesion”, he argues OPEC’s dominance rests on the cartel theory, one rested in “concentration, product differentiation, and barriers to entry” who makes “an agreement about a price or price structure for an industry’s output” (Doran, 1980). With member nations holding significant portions of world supply, OPEC’s behavior reflects that of a monopolist and experience a downwards sloping demand curve, not only strengthening the market power of states but successfully utilizing price cuts, market allocation and bid-rigging as means to supremacy.

Through qualitative and quantitative research, it is evident OPEC plays an essential role in global oil markets and its lasting influence powering the world economy. However, the current scholarly research surrounding OPEC has been primarily focused on black and white characterizations of OPEC being or not being a cartel. Thus, the specific question regarding the extent OPEC fits into the categorization of a cartel, if it does at all, has yet to be spotlighted and assessed in depth, which is what this paper aims to contribute to the current research.

Analysis

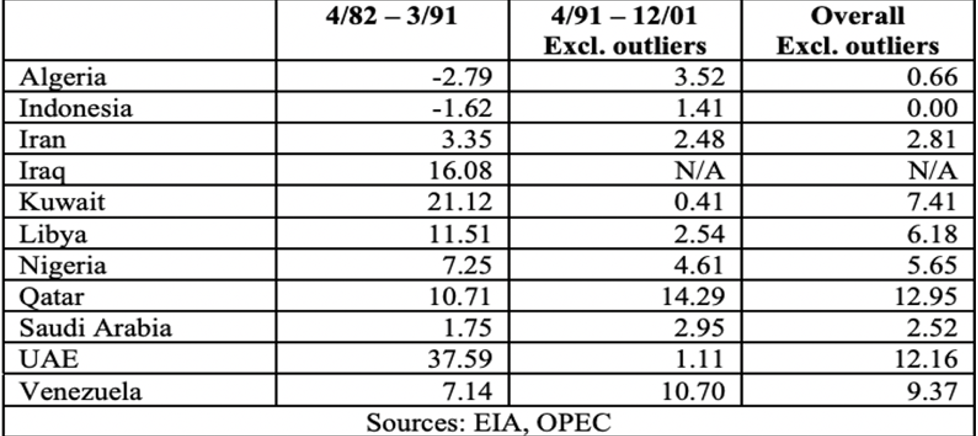

First and foremost, OPEC does not exemplify cartel characteristics because the organization, fragmented by ethnic and religious differences, cannot effectively implement anti-cheating mechanisms within its member nations, allowing the members to freely increase or decrease production at will. The OPEC quota allocation process is determined by each country’s “oil production capacity and imports per capita” and set at the beginning of each year during OPEC member conferences (Gault, 1990). Since these verbal agreements are never written in contractual terms, no international governing body, such as the UN or GCC, has the power to enforce each state’s adherence to their quotas. In fact, OPEC expects countries to carry out the quotas “in good faith, the obligations assumed by them,” but this has raised the issue of the credible commitment and time inconsistency problem, where greed and profit-seeking incentives deviate states from acting rationally in the short run (OPEC). As Sel Dibooglu, Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri-St.Louis, claims, “cheating is a permanent phenomenon” in OPEC countries and cheating happens more in some countries than others (Dibooglu, 2008). To visualize these effects, Duke University’s Pavel Molchanov compiled each OPEC members’ percent deviation from the intended quota limits from 1982 to 2001 (Molchanov, 2003). From the table below, it is evident that Qatar, the UAE, and Venezuela deviated the most during this period with Indonesia almost always following through with their verbal limits.

Table 1: Mean Percentage Deviation from Quota, 1982-2001 (Molchanov, 2003, 6)

Therefore, it is equally important to examine the reasons for these deviations. Oftentimes, cheating occurs when prices are low, and countries compensate by oversupplying production to capture a larger market share (Dibooglu, 2008). Other studies point to countries deviating to “reduce the cost of their oil imports” or to “increase the purchasing power of oil” (Baumeister, 2016). Interestingly, these reasons were all present in 1998 when OPEC requested Qatar to cut production to 384 thousand bpd, but with Qatar continuing to produce at 670 thousand bpd, it led to the further downturn of oil prices in the 1990s and the eventual crowding out of revenue for other nations. (Ghoddusi, 2018). Despite this, the most serious offenders are more likely to be smaller, rotational producers with significantly less market share like Ecuador and Gabon, who “gained notoriety for overproduction and finally deciding to escape the quota system altogether” (Molchanov, 2003). Knowing this, OPEC tries to adjust for this by granting higher quota limits to these countries but to no avail. In addition to OPEC quotas being an unenforceable contract, relationships between member states are often cited as tenuous and fueled with conflict. For these Middle Eastern countries, recent memory, especially within the older generation, has been filled with images of war and ethnic differences exemplified by the multiple oil shocks, the Iran-Iraq War, and the Arab Spring, making it even harder for politicians and representatives to negotiate effectively with deeply entrenched fault lines embedded in memory.

OPEC quota deviations occur because of the lack of dependable accounting mechanisms and deep distrusts within OPEC nations. These reasons have led to the emergence of Saudi Arabia’s dominant presence in the organization, which is the second major reason why OPEC cannot be classified as a cartel.

Saudi Arabia has long been crowned the “dominant producer” in OPEC, possessing the largest known oil reserves, standing at 262.5 million barrels, amounting to one fifth of the global oil supply (Al Yousef, 2010). Moreover, Saudi Arabia is also the largest net exporter of oil, exporting “4 percent of its crude to Europe, 14 percent to the United States, and 45 percent to Asia” and has earned its reputation as the “producer of last resort” (Al Yousef, 2010). These statistics have allowed Saudi Arabia’s state-owned enterprise Saudi Aramco to restrict direct foreign investments and allowed Saudi Arabia’s production numbers to dwarf other nations, a reflection of its international power and pseudo-controller of world prices. The reason Saudi Arabia can position itself as the leading producer is because, unlike other OPEC countries, Saudi Arabia is strategically located between five tectonic plates and microscopic movements in these plates can produce large oil traps and pools along with a natural lift to easily bring oil to the surface. As a result, Saudi Arabia has effectively capitalized on their geographic lottery and the medium-gravity, high-sulfur Arab Light they produce is widely seen as the global oil benchmark, allowing them to experience economies of scale compared to non-OPEC producing nations, who have both lower API gravity and sulfur content in their crude (McKinsey, 2021).

Therefore, it is no coincidence that throughout history, Saudi Arabia has served to preserve price structures and the integrity of OPEC itself. During the Iranian Revolution from 1978-1979, Khomeini eventually consolidated power in the country, but with Iran off the market in terms of oil production, Saudi Arabia made up the slack by increasing its oil production from 8.5 mmbpd to 10.5 mmbpd causing oil prices to jump from $13 to $34 per barrel (Yergin, 2009). In the end, Saudi Arabia was able to cushion the impact of the Second Oil Shock with the result only a 4% to 5% decrease in total world production (Yergin, 2009). Soon after, OPEC enacted a “free-for-all” policy and rid of its pricing structure. However, Saudi Arabia was the only country to hold their prices at official levels, showing its stabilization policy from the Yamani Edict (Yergin, 2009). This shows Saudi Arabia’s absolute scale of oil reserves and how its policy can have an impact on foreign states as seen from the long gas lines and stockpiling in United States. The same can be said about Saudi Arabia’s role during the price collapse of 1985. Declining oil consumption and the “oil glut” defined the eighties and led prices to fall from $30 to below $10 per barrel (Morgan Stanley, 2021). As a result, Saudi Arabia’s “attempts to defend the marker price resulted in a huge loss of market share and revenues” reducing production by more than 6 million barrels per day (Oxford Energy, 2021). These examples have raised the question of the responsibility of other states to ensure price stability in the oil markets; however, this seems to be an insurmountable task with seemingly endless examples of quota non-compliance.

With the rest of OPEC producing significantly less than Saudi Arabia, they are described to be on the competitive fringe of Saudi Arabia’s influence, in debt to its policy whims, all of which have created a tit-for-tat dynamic within OPEC members, as continual salami tactics erode the integrity of the organization itself. This dynamic has concerned international institutions and raised questions of OPEC’s legality as an intermediating body.

Lastly, OPEC is not a cartel because it does not infringe on WTO or OECD mandates while stabilizing the world price of oil at the same time. The WTO seeks to promote trade liberalization and increase transparency in all reporting processes, which seems to pit WTO and the OPEC in direct conflict with the former promoting free trade and the latter seemingly restricting and controlling world supply of oil. Interestingly, nine OPEC members are also WTO members, which convolutes relations and intentions between the two organizations (Bose, 2018). For this reason, scholars such as Stanley Lai have argued to either ratify the international competition laws within the WTO or to create an entirely new institution specifically designed to target oligopolies (Lai, 2008). However, the main reason that the WTO has not interfered with OPEC sovereignty is because WTO law can only govern a natural resource having “passed through a production process and been converted to a product ready for exchange and trade” (WTO, 2021). This means that OPEC’s crude is not under WTO’s jurisdiction since only the manipulation of trade of final products is considered cartel behavior. However, the “moment OPEC countries produce crude and ban its exportation, they would be in breach of their WTO obligations” (WTO, 2021).

Moreover, the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), is a group of 37 countries to “establish evidence-based international standards” and prosecute hardcore cartels that “injure customers by raising prices and restricting supply” (OECD, 2021). The organization has uncovered 75 cartels over the span of six years and found more than 100,000 companies responsible for price fixing (OECD, 2021). With such a thorough investigation lens, the OECD has not intruded OPEC’s sphere of influence because the OECD regards OPEC to be “legitimate efficiency-enhancing integration” that does not “make rigged bids and establish output restrictions” that member countries effectively follow through with (OECD, 2021).

Lastly, OPEC is not a cartel because the organization has also shown a strong history of stabilizing the world supply of oil. The primary objective of OPEC is to maintain stable prices in the long run and OPEC nations have 8 billion barrels of buffer stocks to ensure prices can swiftly recover from adverse shocks, dependent on the International Energy Agency, who requires participating nations to hold stocks equal to 90 days of import (IEA, 2021). Thus, if international prices were derailed, one would “buy when prices are low and sell when they are high, which stabilizes prices and at the same time generates profits”, smoothing out the floor and ceiling price fluctuations and ultimately the commodity cycle (IMF, 2021). Traditionally, cartels have disrupted the global trade of commodities as seen with the diamond, tin, and coffee industries; however, there are also disadvantages for holding buffer stocks. In 1980, the International Tin Council stockpiled 50,000 metric tons of tin in buffer stock, half of which were from unauthorized borrowing schemes. Thus, when the ITC could no longer control the price of tin because of cheap substitutes and new producers not subjected to ITC quotas, the ITC collapsed in 1985 with 900 million in debt (Chandrasekhar, 1989). Additionally, the opportunity cost of holding stocks can pile up, costing countries more money as “price fluctuations can greatly exceed storage costs” (IMF, 2021). Lastly, the existence of these stocks has also led to the creation of the oil futures market, where prices are either contango or backwardation, causing rampant speculation and even more uncertainty. However, as seen with the International Sugar Organization and the Tripartite Rubber Council, the benefits of effectively managed buffer stocks outweigh their drawbacks (Goreux, 1978).

Limitations and Counterarguments

Although the perspectives of international institutions may indicate that OPEC is not a cartel due to its stabilization force, the changes in statistical data since 2001, America’s rise of oil supremacy and the Arab Oil Embargo introduce potential limitations and opposing perspectives to the current research that must be addressed. First, Molchanov’s statistical data regarding quota violations do not account for data from 2001 to 2021, and this period might indicate a shift towards an alignment with verbal quotas, causing a lower standard deviation. In the same vein, the reliability of the data itself is questionable. As countries self-report their production levels to OPEC, many instances have occurred where countries intentionally siphon off their reserves into other markets, blurring the validity of the data (Crane, 2009). Thus, not only does more research needs to be conducted on the topic, but there also needs to be more transparent reporting systems within each country to ensure fair standards. Regarding Saudi Arabia’s dominant producer argument, many claim Saudi Arabia’s hegemony in oil markets is being overshadowed by the United States. As non-OPEC members are slowly gaining a larger share of the market, the relevancy of Saudi Arabia’s sphere of influence continues to wane, especially with the upcoming expansion projects in the Permian Basin and Athabasca Oil Sands (RRC, 2021). Despite this, the United States will continue importing Saudi oil in the long run due to their lower prices and product differentiation of Arab Light crude (EIA, 2021). Lastly, in terms of OPEC stabilizing world markets, critics claim the Yom Kippur War and consequence from the Arab Oil Embargo in the 1970’s as a blatant example of OPEC exerting power beyond its domain. However, not only did the oil embargo not achieve its intended goal of changing foreign policies, the oil weapon employed during this critical juncture proved to “remake the international economy” and was not motivated purely by OPEC intentions, but more so that of ethnic and religious underpinnings (Graf, 2012).

Conclusion

The world has developed a symbiotic relationship with oil, with one seemingly inseparable from the other, which makes the study of OPEC a crucial topic for scholars to uncover the global dynamic of politics and trade. Ever since OPEC’s humble beginnings in Baghdad in 1960, it has now solidified its place among the world as the leading provider of crude oil, possessing the fulcrum in stabilizing the tumultuous oil market. Thus, through examining different perspectives of OPEC’s international policies, one can conclude OPEC mostly serves to ensure the stable price structure consumers experience today. Although the organization does have its intrinsic flaws, it does not definitively exemplify traits of a cartel because it incentivizes members to cheat in the short run, emphasizes Saudi Arabia’s dominant share in the market, and does not infringe on the domain of international institutions. For these reasons, OPEC, on a spectrum, can only best be described as a loosely tied, inefficient oligopoly since countries are more focused on prolonging their regimes than actual output collusion. With that being said, the legitimacy of OPEC is also under threat. With alternative methods of powering the world such as biofuels, natural gas and the sustainable energy transition, more research needs to be conducted regarding effect of OPEC’s market share and whether oil will continue to be the engine of the world in the near future.

Below is my final paper submission for my class on Oil & Energy during the Fall 2021 school year.

Works Cited

Al-Sultan, Abdulrahman. “Alternative Models of OPEC Behavior.” The Journal of Energy and Development, 1993. https://www.jstor.org/.

Almoguera, Pedro. “Testing for the Cartel in OPEC: Non-Cooperative Collusion or Just Non-Cooperative?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2011. https://www.jstor.org/.

AlYousef, Nourah. “The Prominent Role of Saudi Arabia in the Oil Market from 1997 to 2011.” The Journal of Energy and Development, 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24812749?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Baumeister, Christiane, and Luts Kilian. “Lower Oil Prices and the U.S. Economy: Is This Time Different?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2016. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90000438?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Bose, Debadatta. “Case against the OPEC: Analysis from a WTO Law Perspective.” SSRN, 2019.

“Brief History.” OPEC. Accessed December 23, 2021. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/24.htm.

Chandrasekhar, Sandhya. “Cartel in a Can: The Financial Collapse of the International Tin Council.” Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 1989.

Crane, Keith. “Imported Oil and US National Security: Oil as a Foreign Policy Instrument” RAND Corporation, 2009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg838uscc.11?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Colgan, Jeff. “The Emperor Has No Clothes: The Limits of OPEC in the Global Oil Market.” Energy Policy, 2013. http://www.ourenergypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/OPEC-Colgan.2013Mar.Copyedit-IO.pdf.

Dahl, Carol, and Mine Yucel. “Dynamic Modeling and Testing of OPEC Behavior.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 1989. https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/research/papers/1989/wp8917.pdf.

Dibooglu, Sel, and Salim AlGudhea. “All Time Cheaters versus Cheaters in Distress: An Examination of Cheating and Oil Prices in OPEC.” University of Missouri St Louis Department of Economics, 2020. https://www.umsl.edu/~dibooglus/personal/cheat.pdf.

Doran, Charles. “OPEC Structure and Cohesion: Exploring the Determinants of Cartel Policy.” The Journal of Politics, 1980. https://www.jstor.org/.

Gault, John. “OPEC Structure and Cohesion: Exploring the Determinants of Cartel Policy.” Energy Policy, 1990.

Ghoddusi, Hamed. “On Quota Violations of OPEC Members.” University of Cambridge: Faculty of Economics, 2008. https://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/people-files/faculty/km418/IIEA/IIEA_2018_Conference/Papers/Jabal_Ameli_Monetary%20Aggregates%20and%20Policymaking%20in%20Iran.pdf.

Goreux, Louis M. “The Use of Buffer Stocks: The Operation of Buffer Stocks and Their Role in Stabilizing Commodity Prices and Export Earnings.” International Monetary Fund, December 1, 1978. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/022/0015/004/article-A006-en.xml.

Graf, Rudiger. “Making Use of the ‘Oil Weapon’: Western Industrialized Countries and Arab Petropolitics in 1973-1974.” Oxford Academic Diplomatic History, 2012.

Gulen, Gurcan. “Is OPEC a Cartel? Evidence from Cointegration and Causality Tests.” Boston College: Department of Economics, 1996. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.133.9886&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Hyndman, Kyle. “Disagreement in Bargaining: An Empirical Analysis of OPEC.” Southern Methodist University, 2007. https://www.hyndman-honhon.com/uploads/1/0/9/9/109960863/opec.pdf.

IEA. “United States’ Legislation on Oil Security – Analysis.” IEA, July 2020. https://www.iea.org/articles/united-states-legislation-on-oil-security.

Insights, McKinsey Energy. “Arab Light Crude.” McKinsey Energy Insights, 2020. https://www.mckinseyenergyinsights.com/resources/refinery-reference-desk/arab-light-crude/.

Lai, Stanley. “Oil Prices and the OPEC: Is There a Basis for International Action?” Erasmus University Rotterdam, June 2008.

Molchanov, Paul. “A Statistical Analysis of OPEC quota violations” Duke University, 2003. https://sites.duke.edu/djepapers/files/2016/08/paveldje.pdf

OECD, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/about.

OECD. “THE OECD INTERNATIONAL CARTELS DATABASE.” The OECD International Cartels Database, 2012. https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=OECD_HIC.

“Oil Price Plunge in 1986.” Morgan Stanley, 2020. https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/oil-price-plunge-is-so-1986.

OPEC, Statute. OPEC Statute, 2021. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/OPEC_Statute.pdf.

Permian Basin Information, RRC. Accessed December 23, 2021. https://www.rrc.texas.gov/oil-and-gas/major-oil-and-gas-formations/permian-basin/.

Plaut, Steven. “OPEC Is Not a Cartel.” Challenge, 1981. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40720003?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Sampson, Anthony. “Oil and Gas Industry: A Research Guide: Organizations and Cartels.” Library of Congress, 1975. https://guides.loc.gov/oil-and-gas-industry/organizations.

“Saudi Oil Policy: Continuity and Change in the Era of the Energy Transition.” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 2021. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Saudi-Oil-Policy-Continuity-and-Change-in-the-Era-of-the-Energy-Transtion-WPM-81.pdf.

Skeet, Ian. “OPEC: Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics.” Middle Eastern Studies Association Bulletin, 1989. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23060760?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Smith, James. “Inscrutable OPEC? Behavioral Tests of the Cartel Hypothesis.” The Energy Journal, 2005. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41323051?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

“To What Extent Are WTO Rules Relevant to Trade in Natural Resources?” WTO, 2021. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr10_forum_e/wtr10_desta_e.htm.

“U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – Independent Statistics and Analysis.” Oil imports and exports – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), April 2021. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/imports-and-exports.php.

Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2008.

Leave a comment