In this paper, the role of banks and economic cycles will first be defined to provide crucial background information, laying the foundation for our understanding of doom loops. It will subsequently make an argument that low interest rates are the primary driver of doom loops and retail banking regulation should be directly targeted to reduce its impact. Furthermore, additional scrutiny will be given to doom loops’ direct consequences paired with cautionary risk management strategies banks should undertake. Lastly, the paper supplements theoretical models and additional perspectives with lessons stemming from Great Financial Crisis to show that doom loops continue to affect investor psychology and leave an indelible mark on regulations today.

Background and Definitions

From Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank to the Medici’s dynasty, the role of banks has always been to bridge information asymmetry and reduce transaction costs allowing for more efficient decision making through indirect finance. However, over the years, banks have grown – in respect to its size, complexity, and interconnectedness. Although these advances granted convenience, it also came with its own set of complications, including nontransparent operations and vulnerability to shocks. These characteristics have made it even harder for regulators to design a best practice regulation program. Thus, there exists a trade-off between stringent regulation and free-market competition. At times, the balance between the two can be tipped, creating economic cycles in its wake. However, one must question why crisis after crisis, the credibility of ‘never again’ announcement falls on deaf ears.

Explanation of Doom Loops on Banking Regulation

The main reason doom loops arise are due to low interest rates. As interest rates represent “human impatience crystallized into a market rate”, they are the lever to which society’s spending and investment decisions are influenced (Chancellor 2023, 30). Not surprisingly, the keys to such policy rates remain with the central bank. Through conducting monetary policy via open market operations, the central bank ‘creates money’ by buying bonds to stimulate the economy. Also known as quantitative easing, this policy increases the money supply in circulation, lowering policy interest rates as a result (Lecture 1, 55).

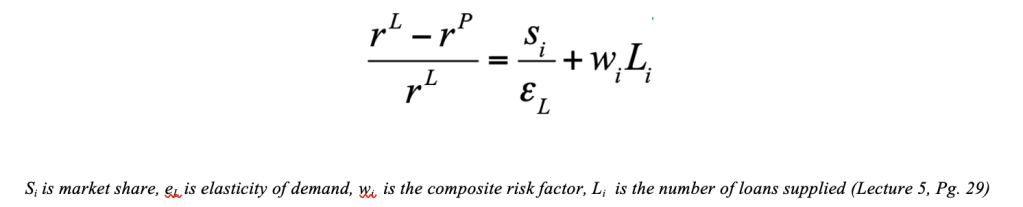

This is different from the lending rate, where the difference (or net interest margin) is dependent upon the composite risk factor and number of loans supplied. This means banks must actively monitor macroeconomic factors in considering markups. According to research conduct by Borio et al. (2015) on 108 banks in Europe, low net interest margins motivate banks to find unconventional avenues to make profit (Coleman 2016). This spurs unprecedented waves of risk-taking by retail banks, starting the doom loop cycle. As a result, the three channels studied below are leveraged investments, utilization of trading books, and securitization.

First, disincentivized by low rates of return through saving, companies actively sought for yield-producing investments, even if it meant sacrificing built-in investment criterion. In the process of doing so, low rates can lead to “excessive leverage and broadly unsustainable asset prices” (Federal Reserve 2017). This trend is most pronounced in buyouts and mortgages, where debt percentages continue to climb within most financing packages.

Secondly, from the retail bank’s perspective, low-rate environments creates an unsustainable frontload of current spending (Chancellor, 43). Therefore, banks become emboldened to increase assets in their trading book, one “made up of financial instruments a bank does not plan to hold to maturity” (Crockett 2023). This development “increases [the bank’s] sensitivity to aggregate market fluctuations” as product prices are directly correlated with market prices (Haldane 2011).

Lastly, banks undergo securitization by selling a portfolio of assets to a special purpose vehicle, “changing the risk profile of the assets on the balance sheet” to appear more liquid (Lecture 5, 45). Although some would argue this method spreads risk through diversification in a less costly fashion, it can lead to worsening moral hazard and adverse selection. This is because “securitization can potentially reduce lenders’ incentives to carefully select, screen, price and monitor borrowers”, causing true risk not to be reflected in credit ratings (Gorton and Pennacchi 1995). With sufficient inertia, low rates can embed itself into investor expectations, perpetuating the dreaded doom loop. This is evident during the 2013 taper tantrum when bond yields rose by a percentage point after Bernanke signaled an end to large scale asset purchases (Brookings 2021). Therefore, officials must rethink regulation to counter the consequences of low interest rate environments and proactively ensure the integrity of the banking system remains intact.

Consequences of Doom Loops on Banking Regulation

It is in the best interest for financial regulators to identify and stem out doom loops through calculated policy enactments. However, the current regulation of retail banking, or lack thereof, has no clear course of action, especially during low interest rate environments.

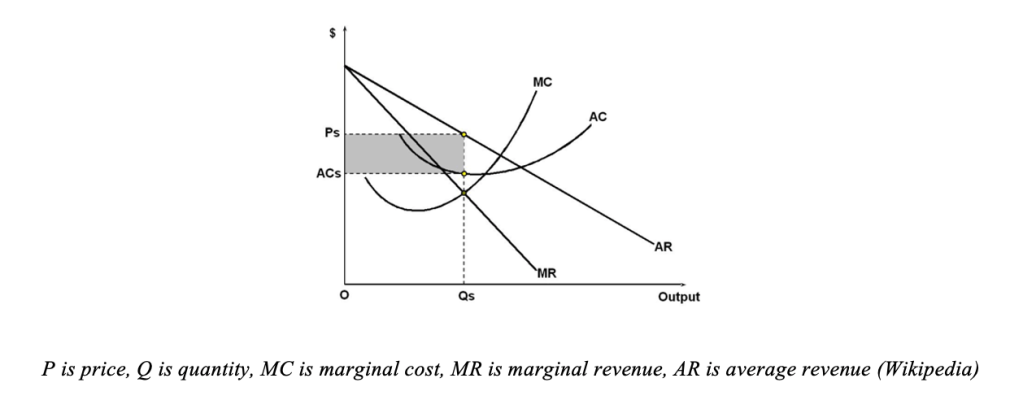

The absence of a coherent plan has allowed retail banking systems to become extremely consolidated through a series of unregulated mergers and acquisitions. For example, UK’s top four banks currently represents 65% of market (Reuters 2018). This is the ideal breeding ground for oligopolies to occur, creating high barriers of entry, product differentiation, and low consumer switch rates (Lecture 7, 11). The diagram illustrated below shows a firm in an oligopolistic market, making profits denoted in gray. The excess in profits are reasons why regulations should be “transparent, consistent, and adaptable” (Lecture 8, 58). For this reason, the market isn’t efficient because goods are priced above MC, meaning resources are not allocated efficiently.

Therefore, banking regulation is an extremely delicate balancing act between handholding but also ensuring free competition with the primary goal of not providing false security to bankers. The result is a regulatory design targeted towards safety nets reconsiderations and legislature.

Safety Nets

Safety nets are “government guarantees provided to depositors and sometimes to all bank creditors” that increase the perceived strength and reliability of banking institutions (Benston 1995). One version of that is deposit insurance. Despite the FDIC insuring $250,000 per depositor, the savings and loans crisis of the 1980s exposed the shortcomings of deposit insurance schemes. Moral hazard enabled by guarantees allowed institutions to take undue risk (Calomiris 1997). As a result, more adequate substitutes are being researched, such as a “risk-based premium” for deposit insurance (Prescott 2012).

Safety nets also come in the form of lending or bailouts. Although critics argue that “support for insolvent banks supports unprofitable activities and undermines the stability of the financial system by transferring losses to other” decades of unregulated mergers have made banks too big to fail (Nicolaisen 2015). Therefore, bailouts remain an effective solution when deployed correctly, which is why researchers are currently employing explainable AI to assess optimal bailout strategies using advanced techniques such as decision trees and bagging (McDonald 2023, UCL 2022).

Legislature

The design of banking regulation has also raised legislative concern. The Basel III framework in 2010 sought to strengthen risk management to prevent future meltdowns (Lecture 10, 20). For example, the leverage ratio of 3 percent was introduced to “reinforce risk-based capital requirements” while the capital conservation buffer ensured banks have “an additional layer of useable capital” (BIS 2014). Domestically, ring-fencing seeks to separate retail banking and investment banking activities, protecting banks “from shocks originating elsewhere” (BOE 2019). Lastly, US legislations like the Volcker rule “prohibits banks from using their own accounts for short-term proprietary trading” (Investopedia). All these restrictions are a consequence of previous doom loops and safeguard our financial system from ruin.

Real World Application

The current design of retail banking regulation is a result of lessons learned from generations of financial contagion. Therefore, to fully understand doom loop psychology, one must examine the most debilitating crisis that led to such drastic reforms. With the benefit of hindsight, the causes of the 2008 crisis can be pinpointed towards low interest rate policy that encouraged risk-taking, accompanied by an unsustainable mortgage market. With bankers reassured by the Fed’s guarantee, the risk-return spectrum was distorted as bankers were blinded by moral hazard. To make matters worse, to the run up to 2008, banks became highly levered, offering complex financial products to subprime borrowers globally. The fall out was a $498 billion bailout worth 3.5% of GDP and saw the likes of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac rise from the ashes (MIT 2019).

The issues discussed in this paper are as relevant as they can be. The recent collapse of SVB questions the reliability of deposit insurance, and decades of turmoil at Credit Suisse brings the question on how to effectively manage internal risk. As a result, this paper aspires to add to the existing literature by arguing low interest rates encourage increased leverage, securitization and trading assets, leading to an oligopolistic market loosely regulated by safety nets and legislature. With a thorough understanding of the causes and consequences of doom loops, it is clear to see how current regulations need to be designed to combat the aftermath of low rates. Then, perhaps we can remain relatively optimistic the next crisis can be averted.

This is my final paper submission for my class on Money & Banking during the Spring 2022 school year at UCL.

Work Cited

Alessandri, Piergiorgio, and Andrew G. Haldane. “Banking on the State.” World Scientific

Studies in International Economics, 2011, pp. 169–195.,

https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814322096_0013. Basel III Leverage Ratio Framework – Executive Summary.

https://www.bis.org/fsi/fsisummaries/b3_lrf.pdf.

Benston, George J. “Safety Nets and Moral Hazard in Banking.” SpringerLink, Palgrave

Macmillan UK, 1 Jan. 1995, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-13352- 9_9.

Bianco, Silvia Dal. “Economics of Money and Banking.” Contains all ‘Lecture’ References. Calomiris, Charles. “The Postmodern Bank Safety Net – Columbia Business School.” Lessons

from Developed and Developing Economies, 1997, https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/ccalomiris/papers/Designing%20the%20Post%20 Modern%20Safety%20Net.pdf.

Chancellor, Edward. Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest. PENGUIN, 2023.

Chen, James. “Volcker Rule: Definition, Purpose, How It Works, and Criticism.” Investopedia,

Investopedia, 19 Dec. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/volcker- rule.asp#:~:text=The%20V olcker%20Rule%20is%20a,funds%2C%20also%20called%20 covered%20funds.

Coleman, Nicholas, et al. “Low Interest Rates and Banks’ Net Interest Margins.” CEPR, 18 May 2016, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/low-interest-rates-and-banks-net-interest-margins.

Crockett, Hans. “Risk Analytics in Banking.” 9 Jan. 2023, London.

Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli. “Do We Need Deposit Insurance for Large Banks?” World Bank Blogs, 2011, https://blogs.worldbank.org/allaboutfinance/do-we-need-deposit-insurance-for- large-banks.

EBA Report – European Banking Authority. https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/document_library/Publications/ Reports/2021/1015682/Report%20on%20the%20monitoring%20of%20Additional%20Ti er%201%20instruments%20of%20EU%20institutions.pdf.

European Central Bank. “Research Bulletin No. 32 – Securitization, Credit Risk and Lending Standards Revisited.” European Central Bank, 30 Mar. 2017, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-research/resbull/2017/html/rb170330.en.html.

Graphics, Reuters. “Britain’s Banks by Market Share.” Reuters, http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/editorcharts/VIRGIN%20MONEY-M-A- CYBG/0H0012Y5G10G/index.html.

Greaves, Mark. “AI Tool Predicts When a Bank Should Be Bailed Out.” UCL News, 17 Nov. 2022, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2022/nov/ai-tool-predicts-when-bank-should-be- bailed-out.

Harbert, Tam. “Here’s How Much the 2008 Bailouts Really Cost.” MIT Sloan, 21 Feb. 2019, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/heres-how-much-2008-bailouts-really-cost.

McDonald, Mark. “Explainability in AI: HSBC Global Research Division.” HSBC Global Research Division. HSBC Global Research Division, 2023, London.

Milstein, Eric, et al. “What Does the Federal Reserve Mean When It Talks about Tapering?” Brookings, Brookings, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up- front/2021/07/15/what-does-the-federal-reserve-mean-when-it-talks-about-tapering/.

“Monopolistic Competition.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Oct. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monopolistic_competition.

Nicolaisen, Jon. “Jon Nicolaisen: Should Banks Be Bailed out?” The Bank for International Settlements, 15 Apr. 2015, https://www.bis.org/review/r150415a.htm.

Pettis, Michael. “Why Does It Matter If Interest Rates Are below the GDP Growth Rate?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 20 Aug. 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/82610.

Powell, Jerome. “Speech by Governor Powell on Low Interest Rates and the Financial System.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2017, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20170107a.htm.

Prescott, Edward S. “Can Risk-Based Deposit Insurance Premiums Control Moral Hazard?” SSRN, 2 Dec. 2012, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2183333.

“Ring-Fencing.” Bank of England, 23 June 2022, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential- regulation/key-initiatives/ring-fencing.

Leave a comment