For most of us, the ability to pay is something we don’t consciously think about. With the swipe of a credit card, we have our merchandise in hand. However, payments are crucial in that they are the way we include and exclude from society. With more than 1,600 banking deserts (defined by the absence of banks within a 10-mile radius) across the US, hundreds of thousands of people are excluded from this seemingly efficient payment system. The inability to pay comes with the inability to sufficiently sustain a baseline standard of living.

This is just one problem that exists within the increasingly relevant payment infrastructure business that Leibbrandt and De Teran detail in The Pay Off. As I read their book, I was taken aback by the little understood world of paying, and how the evolution of payments also became our greatest challenge.

It is commonly understood that money is “one of the three key abstractions that enable societies to function beyond the scale of prehistoric tribes, along with religion and writing.” Yet despite the prevalence of money, there remains a gulf between how society thinks the money world works and how it actually works. As a result, the authors’ main purpose is to “narrow the gap between our dependency on payments and our awareness about them.”

Personally, I was surprised to learn that when we think about transferring money, we are essentially changing entries in ledgers while the money itself doesn’t move. Money, therefore, can be thought of as transferable debt. My money at Chase is nothing but their debt to me. If I were to transfer money from my Chase account to my brother’s Citi account, I’ve just transformed Chases’ debt owed to me into Citis’ debt owed to my brother. I was also intrigued by the sentimental value of cash around the world. For example, the authors cite only 10% of total transactions in Sweden are paid by cash. This has heralded an era of efficiency but has sparked a so called ‘War on Cash’, where resistance groups such as the Cash Rebellion have taken a vocal stance against this gradual eradication. On the other hand, there are countries like Albania who use cash in 99% of their transactions, which is estimated to cost the country 1.7% of its GDP per year. From the perspective of either extremes, it is clear to see physical cash is hard to completely phase out, even with its high costs. These examples have made me think about if the world can completely transition to a cashless society. As a proficient user of WeChat Pay myself and having seen China’s transition, I am interested to see if cashless societies are replicable elsewhere. From Sweden’s example, I’ve learned whether or not a country can transition into a cashless society doesn’t solely depend on existing infrastructure but also upon cultural and societal norms. The most important consideration in these norms is a society’s willingness to forgo privacy for efficiency.

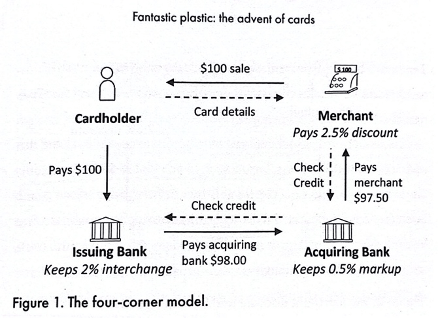

From money laundering to cryptocurrencies, this book has also sparked introspection as I reflect on my digital footprint with my handy Bank of America credit card. With the advent of the first credit card in Major’s Cabin Grill in New York in 1950, credit cards and the four corners business model have become one of the driving technologies pioneering growth in the modern era. The graph is drawn from the book and the author explains it as follows:

Let’s pretend the cardholder bought a $100 meal at his favorite Korean BBQ shop. When he takes out his card to pay, his bank takes an interchange fee of 2% ($2). This interchange fee allows the bank to offer incentives to its card customers, such as cashbacks, air miles and lounge access. The $98 then goes to the acquiring bank, who takes a 0.5% markup fee. The result is $97.5 reaching the merchant. This means merchants must account for these fees and raise the prices on his menu to reflect these changes. So even though we don’t see explicit card fees on our transactions, we are paying for it in the form of higher prices. This is one of the ways card companies make money. Some others are the lucrative business of compounding interest bills, foreign exchange fees, overdraft fees, and general service fees for having access to amenities.

In doing some of my own research, I’ve learned that some fintech companies in the recent years have eliminated a party from this model and created its own version – the three corners model. Exemplified by Klarna’s ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Slogan, Klarna allows consumers to pay for goods in installments of four, all interest free. Thus, Klarna takes on the initial payment and trusts the consumer to pay back after a brief credit check. This is just one example of how fintech is disrupting the traditional banking industry. Stripe, Chime, Sofi, Venmo, and Wise are just some more examples of disruption to come. With the power of innovation, a lean team and less regulatory oversight, it will be exciting to see how the battle for modern banking plays out.

However, both the four and three corner models raises the same question: to what extent are our digital footprints tracked? Furthermore, with our income and spending laid out on spreadsheets for the world to see, can payment data become weaponized? This is certainly the case for countries, where Chapter 28 details Iran’s exclusion from the international financial system as a result of its refusal to limit its nuclear development program. However, on an individual basis, the possibilities are endless. Tracking payments has allowed police to track down the intricate web of Pablo Escobar’s drug network as well as Huawei’s CFO Meng WanZhou on charges of bank fraud.

Lastly, the book covers financial fraud as its last chapter focusing on Lazarus Group, an alleged North Korea hacking group that broke into the internal network of the Bangladeshi central bank in 2015. Lazarus sent job inquiry emails with CV’s containing malware, where they soon had a grasp on their entire software system. Over the next few days, Lazarus sent out 35 payment instructions of value well over $950 million to international banks via SWIFT. Most of the orders were stopped at its tracks, but well over $20 million were diverted to the Philippines, where they were laundered through casinos and into the hands of the hackers. Attacks like these bring into question the reliability of our banking transaction services and the additional regulation and anti-laundering initiatives that needs to be in place.

It is hard to cover the whole book in its entirety as the authors provide a such a broad overview of the industry. From Facebook’s experiment of Libra to Kenya’s launch of M-Pesa, the mere volume and complexity of the topic showcases the importance of understanding the payments industry and how it is ever-evovling with new technologies. I hope through my intentional exclusion of discussing certain areas of the book, you as a reader are motivated to pick it up yourself.

Nevertheless, one thing is certain: without the ability to pay, we are left stranded. As the author says: “payment data will be the new oil.” If you can track everything everyone is buying, selling, making, and transferring, what else can you not do?

The Pay Off: How Changing the Way We Pay Changes Everything.

By Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha De Teran

Leave a comment