I’ve always been very interested in aspects of the world that are invisible to the consumer. In the past year, I have indulged in books relating to chip manufacturing and commodity trading just to name a few. So, when the chance arrived to learn more about the invisible highways and logistical networks that ensure our Christmas gifts arrive on time, I decided to jump on the opportunity and take a deep dive into this novel world of supply chains.

This is a story on how broken supply chains and surging inflation will sink the global economy. By starting his book with the all-to-familiar scene of bare shelves and high prices, Rickards cites a host of factors causing supply shortages we continue to experience today. From the onset, Rickards takes a pessimistic view of our current supply chain and claims it will be a matter of five to ten years before it is fully rebuilt into what he calls Supply Chain 2.0.

Supply chains are not a new invention. Throughout history, we have seen them used by Alexander the Great to conquer the Greek peninsula and by Eisenhower upon landing in Normandy on D-Day. These actors always had to deal with uncertainty, piracy, and the chance their goods might not arrive in time. Therefore, although supply chains are not new, the science behind them are.

Rickard starts with an overview of the industry as it stands. As we have entered the information era, a range of technologies have surfaced including advanced logistical tracking software Logink, models to predict supply and demand, and buzzwords such as just-in-time inventory, intermodal transportation, and cross-docking. The result is a hyper-efficient, data-driven supply chain that eliminates redundancy and cost. This is exemplified by companies being able to employ one-day shipping, even from halfway across the globe.

However, with efficiency, we reduce our resilience to shocks. In our pursuit of building a supply chains with the least number of nodes or middlemen, we run the risk of disaster if one of those connections breaks down. This trend is most pronounced in semiconductor and automobiles with thousands of parts having to be shipped to a warehouse just in time for assembly. Thus, Rickards claims that “an uncontrolled cascade of failure is exactly what we see in global supply chains today.”

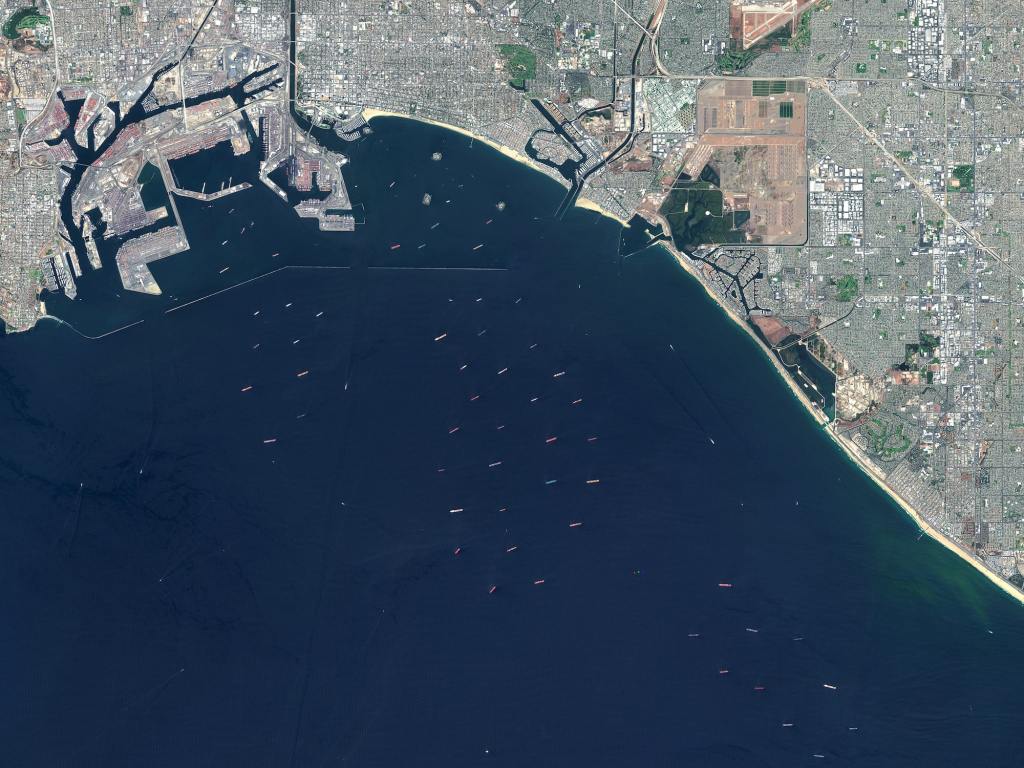

I can barely even fathom the interconnected of my own personal life. Just to take an example of my day: I wake up in a mattress made from China, drink my coffee from Colombia, and drive my German car to an American school. And within each of those components, lay its own, more complex supply chain. Thus, I can only imagine the amount of planning it takes to recognize, order, ship and receive goods between countries. Rickards puts this into perspective by analyzing the bottleneck in the Port of Los Angeles in 2021.

At its worst, the Port of LA saw its ships having to wait 10 or more days before being able to dock. Although many thought this had to do with the workers not working hard enough, it was just the opposite. The capacity in the unloading units (where cargo can only be stacked six high) only could accommodate 18,000 shipping containers. With more than 550,000 containers waiting to be unloaded, it is clear to see why this increased the cost of goods sold, also called demurrage.

Paired with a shortage of drivers, bad weather, and the COVID vaccination restrictions, the problem only compounded in complexity and contributed to global inflation.

To get to the root of the supply chain bottleneck in 2021, Rickard dismisses COVID-related problems and instead points to Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017 as the culprit. Soon after his withdrawal, Trump imposed $50 billion worth of tariffs on Chinese imports. China did the same and implemented a 15% tariff on 120 US products. The result was an overflow of goods to get to its destination before the grace period (time before tariffs were implemented). The trade war between China and the US also led to a reconfiguring on shipping lines and unlikely new alliances. Take soybeans as an example. China stopped buying soybeans from the US and found a new trading partner, Brazil. This resulted in a shifting of martime carriers, port embarkations and trading partners. These swift changes only added more stress to the already delicate supply chain in 2017.

Rickards builds on this argument, claiming that this new supply chain is one where China is excluded from the picture. He cites Xi’s aggressive stance of its nation’s technology companies, its detrimental Zero Covid policy, high income inequality, real estate bubble and dependency on energy as its main weaknesses.

However, I’ve recently been thinking about the legitimacy of his argument. We see capital flight from China despite its best efforts to contain its money internally, highlighted by the number of family offices migrating from Hong Kong to Singapore. We see large multi-national companies such as Samsung and Nike decreasing their investment in China and moving to countries like Vietnam with a more stable political climate. This is epitomized by Apple’s Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou, where thousands of workers clashed with police after tensions regarding unpaid salaries and COVID restrictions.

However, I remain optimistic that China will be a dominant player in the newly constructed supply chain to come. Not only will the low-cost, mass-produced option continue to entice foreign investors, China’s new Five Year Plan promises investments in green development, artificial intelligence, semiconductors and nanotechnology. I also see potential geopolitical alliances and economic opportunities from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Although some critics cite China’s debt-trap diplomacy, connecting both land and sea routes with China-backed infrastructure projects will only open the door to increased trade activity by untapping new markets.

It is clear to see geopolitics and economics are deeply interlinked, with supply chains sitting in the center of that conversation. Therefore, to understand supply chains is to understand the state of the world and where it is heading in the next ten years.

I wanted to end with one of my favorite quotes from the book: “A supply chain is not an object. It is a process. There is no one right way to build it but there are thousands of ways to end it.”

Sold Out by James Rickards

Leave a comment